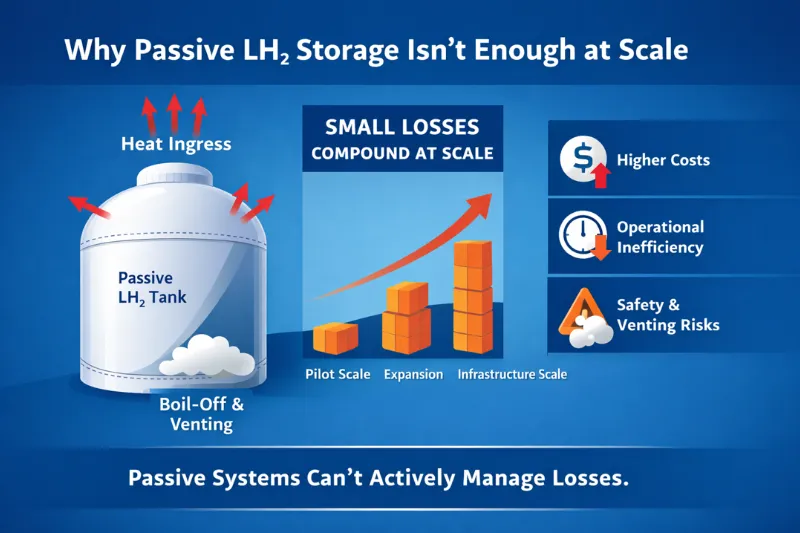

Why Passive LH₂ Storage Isn’t Enough at Scale

By: GenH2 Staff

Read Time: 0 minutes

This article is part of a GenH2 thought-leadership series exploring the fundamentals of liquid hydrogen storage as hydrogen infrastructure scales—from loss prevention to real-world deployment.

As liquid hydrogen (LH₂) moves from research and pilot projects into real-world energy infrastructure, storage performance becomes a defining factor. While passive LH₂ storage systems have played an important role in early deployment, their limitations become increasingly clear as scale, duration, and operational demands grow.

This is especially relevant for energy storage, transportation fueling, and industrial applications—where efficiency, reliability, and predictability are essential.

How Passive LH₂ Storage Works

Passive liquid hydrogen storage relies primarily on insulation and tank design to limit heat ingress. No matter how advanced the materials, some amount of environmental heat inevitably enters the system. Over time, this heat causes a portion of the liquid hydrogen to warm, vaporize, and increase tank pressure.

To maintain safe operating conditions, excess pressure must be relieved—typically through venting. This process protects the system, but it also results in the loss of usable hydrogen.

Why Scale Changes Everything

At small volumes and short storage durations, boil-off losses may appear manageable. However, as storage capacity increases, even minor heat leakage becomes more pronounced.

At scale:

- Small percentage losses translate into large absolute fuel losses

- Venting becomes routine rather than occasional

- Operating costs and logistics complexity increase

- System efficiency declines over time

For infrastructure-scale systems, these losses directly impact economics and long-term viability. What works in a demonstration environment may not hold up under continuous, real-world operation.

Passive Systems Are Reactive by Design

A key limitation of passive storage is that it reacts to heat ingress rather than preventing its effects. Insulation slows heat transfer but does not remove it. As a result, evaporation is not a possibility—it is an inevitability.

This reactive approach places limits on the duration of hydrogen storage, the predictability of delivery, and the efficiency with which energy is retained.

Why This Matters for Energy Storage

Hydrogen is increasingly viewed as a solution for long-duration energy storage—converting excess renewable electricity into a fuel that can be stored and used later. In this role, storage losses directly undermine the value proposition.

Energy produced but not retained cannot be dispatched when needed. For hydrogen to function as a dependable energy carrier, storage systems must preserve the fuel—not gradually diminish it.

Moving Beyond Passive Storage

As hydrogen infrastructure expands, the industry faces a clear inflection point. Scaling hydrogen production alone is not enough; storage systems must evolve alongside it.

Preventing losses requires moving beyond passive acceptance of boil-off toward approaches that actively manage tank conditions. This shift enables greater efficiency, improved operational control, and more predictable system performance—qualities that are essential for infrastructure deployment.

Setting the Stage for the Next Phase of Hydrogen

Passive LH₂ storage has served the industry well during the early stages of adoption. However, as hydrogen applications demand larger volumes, longer storage times, and tighter cost constraints, its limitations become more pronounced.

The future of hydrogen depends not only on how cleanly it is produced—but on how effectively it is stored.

In the next post in this series, we’ll explore what loss-free liquid hydrogen storage makes possible for renewable energy integration and large-scale clean energy systems.

To learn more, download our Controlled Storage eBook.

About this series: GenH2 advances liquid hydrogen infrastructure by contributing engineering insights and industry perspectives. This series is intended to support informed discussion around hydrogen storage challenges and opportunities as the energy transition accelerates.